Why We Should Stop Using “Good Touch, Bad Touch” and Switch to “Safe and Unsafe Touch”

I’ve been researching what types of resources would be most helpful, as I have just set up a Teachers Pay Teachers account to support teachers, educators and parents who homeschool, with best-practice resources.

I noticed on Teachers Pay Teachers and Pinterest just how many resources are still using good touch, bad touch.

It’s 2025, and we now know so much more about the language we use when teaching children about body safety. Despite this, I continue to see outdated terminology like good touch, bad touch still being used in many child protection resources. While this may seem harmless on the surface, the reality is that this phrasing can be confusing, misleading, and even harmful to children.

At Safe4Kids, we use safe and unsafe touch instead, and there are very good reasons why. Let’s dive into why this change is necessary and how it helps children better understand their rights and personal safety.

1. The Problem with “Good Touch, Bad Touch“

For years, many child protection programs have used the phrase good touch, bad touch to teach children about personal boundaries. While well-intentioned, this approach has several significant flaws:

a) Abuse Doesn’t Always Feel “Bad”

One of the biggest misconceptions about abuse is that it always feels uncomfortable or painful. The reality is that many abusers groom children, making inappropriate touch feel pleasant, safe, or even special. If a child has been taught that a bad touch is one that feels wrong or hurts, they may not recognise that what is happening to them is abuse.

For example, if a trusted adult or family member is touching them inappropriately but framing it as affectionate or loving, a child may not categorise it as “bad” and, therefore, may not disclose the abuse.

b) It Can Be Confusing for Children

Young children are very literal thinkers. If they are told that certain touches are bad, they may assume that means they should never happen, even in appropriate situations. This can lead to confusion, guilt, and shame when they receive normal, healthy touches like a doctor’s examination, a hug from a parent, or being helped with toileting as a toddler.

If an abuser tells them that what they are doing is “good” or makes them feel special, the child may not associate it with the bad touch they’ve been warned about.

c) It Can Lead to Secrecy and Shame

Children who experience abuse may feel guilty or ashamed if they don’t recognise the touch as bad at first. They might think, “I didn’t feel bad, so maybe I was a willing participant,” leading to self-blame. If we label touches as good or bad, children may struggle to report abuse because they think they have done something wrong, that they are bad.

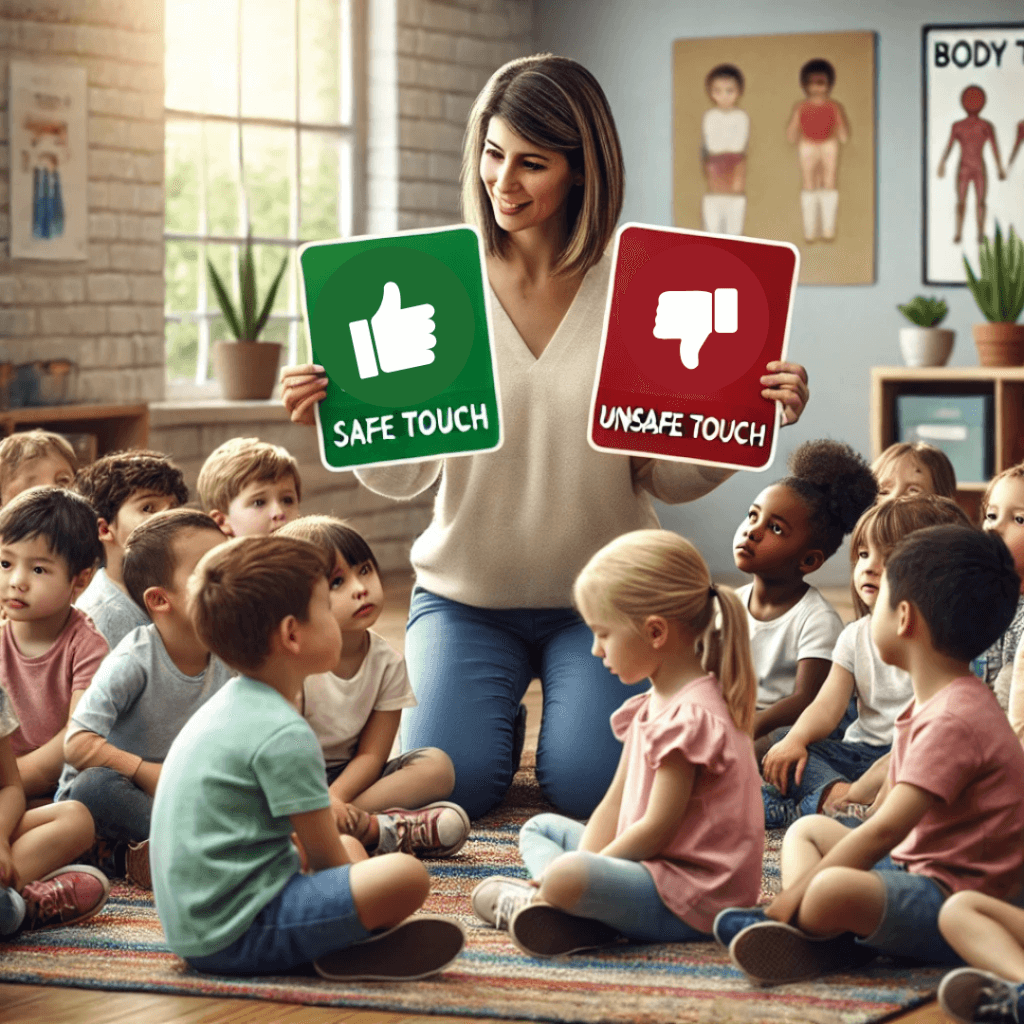

2. The Benefits of Using “Safe and Unsafe Touch”

To address these issues, the Safe4Kids program teaches safe and unsafe touch instead of good touch, bad touch. Here’s why this shift in language makes a big difference:

a) Clearer and More Inclusive Language

Using safe and unsafe removes the moral judgment from the equation. Instead of associating touch with good or bad, which can carry subjective or emotional weight, this approach simply classifies touch based on whether it respects a child’s body and personal boundaries.

- A safe touch is one that helps keep the child clean and healthy or helps the child feel loved in a respectful way, like a high five, a hug (if they want one), or a doctor checking an injury.

- An unsafe touch is one that makes them feel uncomfortable, scared, or confused, like someone touching their private parts, hitting them, or touching them without consent.

This removes the need for children to make a subjective judgment about whether a touch is good or bad and instead focuses on their feelings and safety.

b) Empowers Children to Trust Their Feelings

The concept of safe and unsafe touch helps children identify their Early Warning Signs, those physical responses (like a racing heart, sweaty palms, or butterflies in their tummy) that signal when they feel unsafe.

By teaching children to recognise and respond to their discomfort, we empower them to seek help even if they can’t fully explain why they feel unsafe.

c) Supports Consent and Body Autonomy

The safe and unsafe model naturally leads to discussions about consent and body autonomy. Children learn that they are in charge of their bodies and that they can say no to any touch that makes them uncomfortable, even from people they love or trust.

For example:

- A grandparent insisting on a hug? The child can say, “No, thank you.”

- A sibling tickling them when they want to stop? They can say, “Stop, I don’t like that.”

- A doctor needing to check a private part? The doctor (or parent) should explain why it’s necessary, and the child should be involved in that decision.

This reinforces the idea that children have a right to feel safe all of the time.

3. What Should We Be Teaching Instead?

If we’re not using good touch, bad touch, what should we be teaching children instead?

Here’s what the Safe4Kids program recommends:

- Teach children the correct anatomical names for private body parts. This helps them clearly communicate if something happens and removes secrecy around these topics.

- Explain that private parts are “just for you” and that no one should touch or ask to see them unless it’s to keep them safe and healthy (e.g., a doctor with a trusted adult present).

- Teach children the difference between safe and unsafe touch using concrete examples:

- 👍Safe Touch: Holding hands with a friend, a high five, a hug (if they want one), a doctor checking a sore throat.

- 👎Unsafe Touch: Someone touching their private parts, someone hitting them, an unwanted hug or kiss.

- Encourage children to listen to their Early Warning Signs and trust their feelings. If something makes them feel uncomfortable, they have the right to say no and tell a trusted adult.

- Help children develop a Safety Team, five trusted adults they can go to if they feel unsafe or need to talk about something.

- Reinforce the “We Can Talk With Someone About Anything” rule so children know they can always tell a trusted adult if something makes them feel unsafe, even if they’ve been told to keep it a secret.

4. Moving Forward: Making the Shift in Schools and Resources

It’s time for educators, parents, and child protection professionals to retire outdated phrases like good touch, bad touch and adopt the safe and unsafe touch model. This shift makes conversations about body safety clearer, more effective, and more empowering for children.

If you’re an educator or caregiver looking for best practice resources, I’ve set up a Teachers Pay Teachers account to provide high-quality, up-to-date materials based on the Safe4Kids Protective Education Program. These resources are aligned with modern child protection principles and help children develop the skills they need to stay safe in a way that is age-appropriate, clear, and empowering.

Let’s work together to ensure that every child receives the best possible protective education—one that truly keeps them safe and gives them the confidence to stand up for themselves.

💡 Want to learn more? Enrol in the Safe4Kids Child Abuse Prevention Education Online Training Course to gain a deeper understanding of how to teach these concepts effectively.